Healing is a matter of time, but it is sometimes also a matter of opportunity.

— Hippocrates

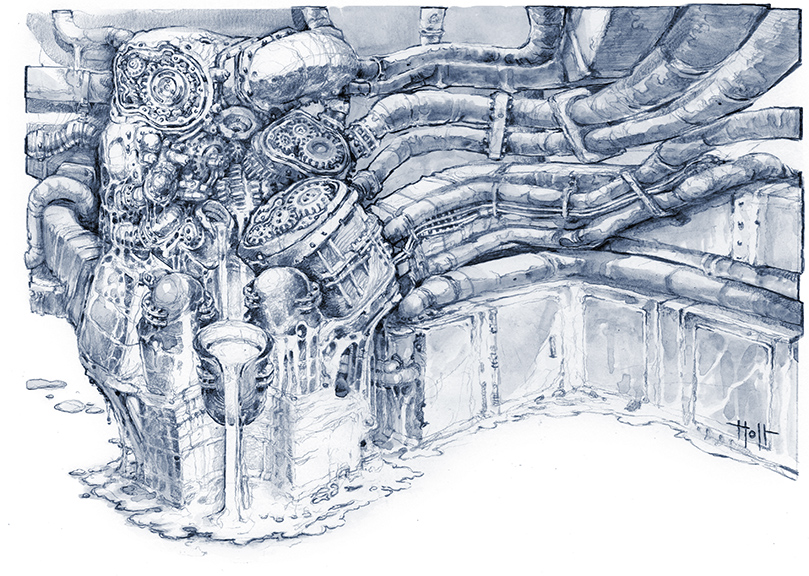

The God-Machine is sick. The God-Machine has always been sick. The God-Machine will, someday, become sick. It’s hard to tell with an entity that so flagrantly violates causality. Ultimately, the Contagion is as universal as the God-Machine that hosts it. There is scarcely a place on Earth the God-Machine hasn’t touched at one time or another, and therefore there’s scarcely a place on Earth that couldn’t host an outbreak of the Contagion. All scholars of the Contagion can really say is that history is replete with breakouts, moments where cultures and even reality itself collapsed around a point, or a person, or a practice.

Accounts of unexplainable events on such a scale stretch back as far as ancient Mesopotamia, where we first know of writing as a common practice, and therefore where written history begins. Some believe that the flood myth itself, present in so many cultures, reflects a massive, ancient outbreak, one which nearly ended the world, that is only preserved in oral histories. Not every historical record of a cataclysmic event represents the Contagion breaking through into our world through the vector of the God-Machine’s Infrastructure, of course. Earthquakes, volcanoes, meteors, and all manner of perfectly natural disasters are capable of presenting as an out-of-context problem in ancient records or literature. The Sworn, however, are not an entirely modern phenomenon themselves; contemporaries of these events, ancient or otherwise, did what they could to stem the Contagion’s spread — and must have seen some success, or, their modern descendants say, they would not be around to talk about it.

Five outbreaks in particular, however, are most relevant to the modern day, and specifically to the five factions of the Sworn, some of whom can claim traditions (if not contiguous organization) stretching back more than two thousand years. None of the factions sprang fully-formed into being. Instead, they were the result of like-minded individuals coming together in the wake of apocalyptic events, and together creating an idea that would, despite lurking only in the shadows of the world, endure the test of time. When the Sworn argue amongst themselves, more often than not these five outbreaks are the ones cited as proof that one faction or another has the right of it.

San Lorenzo Colossal Head 11: 900 BCE

The Head is massive, with details finer than any other colossal head. Even Tu, the last Olmec king seated on a crumbling throne, didn’t know which of his ancestors commissioned it. The Head had always existed, bearing the likeness not of a king, but a god. This divinity was not named, not known like the Dragon or the Feathered Serpent. It was not listed amongst the great Eight, or even any of the lesser Gods his people revered. Yet it sucked up all prayers and all life, leaving the island in the middle of the Coatzacoalcos River barren. Tu could see the future, full of desolation and endings, as clearly as he could see the gleaming metal and polished, ivory human bone behind the head’s stone facade.

The San Lorenzo Colossal Head 11 is a secret of archeology. While San Lorenzo Colossal Heads 1 to 10 are on display for tourists, the eleventh head was sequestered away when testing revealed metal alloys undiscovered by man, and elements not on the periodic table, laced in the stone. All public records of it were suppressed, though rumors and pictures survive on the Deep Web. Attempts to carbon-date it consistently fail. The head’s features are Olmec, with a broad nose and full lips, although it is more androgynous than other Colossal Heads. Large discs stretch the ear lobes, and the mouth gapes open wide as if it hungers. Its headband is incredibly detailed, full of maze-like patterns and tableaus of worship. Efforts to document the scenes portrayed in the headband have likewise failed. The sheer volume of detail, untraceable lines and figures wedged together, wears on the observer’s mind. Since its discovery, archeologists have identified 1) a city of curving spires rising towards each other from the ground, 2) human figures worshiping a towering creature with arms so large they reach the ground, and 3) a head resembling Colossal Head 11, mouth opened wide as lines of humans walk into its maw. A handful of observers have recorded different tableaus, alternating widely between a beautifully ordered utopia and a barren wasteland, but the three above are the only ones seen by more than one person. Mages, believing the Head to represent an Exarch and doing their own investigation, have had more luck.

The Head hails from the first Olmec City circa 1150 BCE. No amount of divination can reveal its creator, and none of the known San Lorenzo kings match its physical features. It’s the tallest of eleven San Lorenzo heads, at twelve feet, and impeccably detailed. The Head spoke when it was finished and unveiled, delivering a message in the first language. Priests flocked to the Head, always rushing back to the safety of their known gods once they gleaned the Head held both the end and salvation of all things. Subsequent kings ordered it buried, placed in a temple overlooking the city, and thrown in the river. None recorded its message, for those who understood could not remember it, and those who remembered could not understand it. It sucked up prayers intended for the true gods, drove kings to madness and greatness, and slowly spelled out demise. This was its Contagion: it trapped the city between the erratic extremes of obsession until it consumed all else. The skills of stonemasonry and agriculture, passed down for five centuries, faded against the presence of the Head. People forgot to eat. Children starved in their baskets as mothers were so closeto deciphering the god’s riddle that all else needed to wait. Kings sat on their thrones, so lost in thought that they were unable to govern the city, the answer lying forever just beyond their grasp. The first Olmec went into decline and was abandoned around 900 BCE, dying on the soft whisper of obsession consuming everything else.

The First Language

The first language is the code that governs the God-Machine’s programming, the Celestial Ladder, and the essence of Creation. It transcends time and space, and those who first mastered it tore it into a thousand pieces so none could follow them on this path to ascendant power. Azothic Memory retains fragments of it though, allowing Prometheans to master the dominant language of their surrounding as the first language is the root of alllanguages. This also grants all Prometheans +2 on checks to identify the San Lorenzo strain, and gives the Tammuz a further +1 bonus to resist infection.

Survivors took the Head’s feverous message with them as they left the ruins of the first city. They still did not understand its message, nor could they remember it any more clearly than a dream fading fast against the world’s light. None of them had even been alive when the Head first made its appearance, yet the Head reached for them through the stitches in time, taking them back to that first and only time it spoke. It carried on in their blood and wormed its way into their minds: The message must be understood. Where they went, Contagion followed. Sculptors throughout Olmec civilization worked bloodied fingers to the bone, sacrificing life and sanity, in an effort to re-create the Head of God. Not until the fall of La Venta, the last great Olmec city, did this strain of San Lorenzo 11 stop.

Unfortunately, the disease lingered and mutated in the earth itself. It re-emerged when the Aztecs built their city of Ten?chtitlan near the site of the lost city. They did not create any Colossal Heads, but instead turned to blood and sacrifice to decipher the message. They came close too, warriors and kings self-mutilating to read the God’s portents in the enlightenment of pain. They thrived as they solved the paradox of the message, which held both Contagion and its cure, and created an empire that spanned the Valley of Mexico. Perhaps in the vast multitudes of time and space, Contagion ended here, five centuries after the first recorded outbreak. Time is also linear though, and whatever progress the Aztecs made was buried alongside them by the cruelty of Hernán Cortés.

The Rosetta Society

The San Lorenzo outbreak spread when the city fell, embedding itself in survivors’ genetic codes and passing through contact in the form of an all-consuming obsession to decipher the message. The Olmecs suffered from it, as did the Aztecs, the Mayans, and Mesoamerican cultures like the Toltecs and the Totonac. So might the Rosetta Society, which claims Mesoamerican origins and certainly exhibits a singular focus on interpreting the meaning behind Contagion, also be infected? The answer is up to the Storyteller. It’s been a thousand years since the Mayans contained the San Lorenzo outbreak, and even Contagion could simply lose its virulence over that time. If it did carry into the Rosetta Society though, the San Lorenzo strain exhibits as the Obsession Condition in addition to the Carrier Condition. Given how insidious the San Lorenzo strain is, exhibiting as mania and eventually leading to a mental breakdown (both common enough in Sworn as it is), neither the Rosetta Society nor the other Sworn have reason to believe they’re infected.

If the San Lorenzo strain did survive inside the Rosetta Society, it remains hidden from the other Sworn. This could either be due to a mutation of the disease, or because the strain, one of the oldest in the world, has lost some of its virulence and is now easily overlooked. In this case, Sworn might not see it until it’s too late and all of the Rosetta Society is infected, or if they have active cause for suspicion and take a very close look. This hidden strain would reduce the Prometheans’ bonus to recognize it to +1, though the Tammuz do keep their bonus to resist it.

The Mayans had more luck surviving the ages, though they face marginalization and discrimination in contemporary Mexico. But their luck ran dry in deciphering the message. They searched for its meaning in blood, in ball games, and in the stars. They came close in Uxmal, the thrice-built city, where they grasped the last remnants of the San Lorenzo strain and buried it deep within the Magician’s Pyramid. The project consumed four hundred years, with building starting in 600 CE and ending in 1000 CE, and a single night as a magician erected the pyramid to escape a death sentence. It took three pyramids, layered inside each other like eggs within eggs. But finally, it was done: Contagion distilled through blood, earth, and air, and contained within a great, near-impenetrable pyramid. Containment is not a cure, but it sufficed for the Mayan people and no outbreaks of the San Lorenzo strain have been recorded since. If Mages worry what the Spanish might have taken with them when they looted the Magician’s Pyramid during their conquest of Yucatán, that is certainly no fault of the indigenous people.

The Contagion Chronicle is currently on Kickstarter.