Greetings all, Matthew here again with another blog! This time we’re entering the thrilling world of international espionage, where you’ll come up against all manner of alphabet agencies, rogue governments, secret societies, and eccentric tyrants bent on world domination.

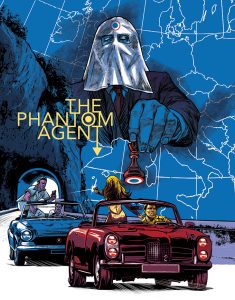

I am of course talking about They Came from [CLASSIFIED]!

I love all the They Came From… games (especially the one we’ll be putting on crowdfunding very soon), but [CLASSIFIED]! holds a special place for me as our finest game in terms of tonal strength. I feel we really captured the essence of gentleman spies, swinging ‘60s, gadgeteering, and megalomaniacal villains in our book, which you can still pre-order over on Backerkit, right here: https://double-feature.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders/

But something I was asked recently was “how do you establish that tone when you’re running this game?” In theory, it’s easier to write on the page than convey at the gaming table. What’s more, that same person asked “how do I come up with a plot?”

Well, that second question is certainly broader, but there’s an easy answer we explored in the Onyx Pathcast, when watching a dreadful Hercules movie and a pretty mediocre spy film: you take the plots you love from existing media (episodes of The Man from U.N.C.L.E., Mission: Impossible, and The Avengers are fertile territory for this, as they have an ageless quality and often exist as one-off bottle episodes) and make them function within your [CLASSIFIED]! Game. To take an example, I ran a hybrid of the Avengers episodes A SURFEIT OF H2O and THE POSITIVE NEGATIVE MAN for the fine folks of Red Moon Roleplaying right here: https://youtu.be/hDWVdxAc0N0

You should feel no guilt in cribbing plots from existing media for They Came From, because that’s what the game’s all about. It allows us to explore our favourite movies, TV shows, video games, plays, novels, and more, and unashamedly so.

In terms of how to establish the tone for your players (how comedic do you make it, how many smutty jokes do you lace in a corset of innuendo, how under threat should the protagonists be, etc.) there’s no better explanation than text we’ve already written for the Director’s Chair chapter of the book. This – along with the rest of manuscript – is available to anyone who pre-orders, but is also right below this introduction! I won’t include the entirety of the chapter, but a useful portion for those of you who want to run your own games.

The Spy Game

Theme

“Theme” is our fancy way of saying “what this game is about.” For TCfC!, the themes are escapism and camp action. These spies aren’t the kind that sit around a desk, reading files and writing reports to send to superiors. They travel around the world! They meet interesting people! They use exciting gadgets to kill those same interesting people! The audiences for these films aren’t looking for the psychological torment that comes from pretending to be someone else for long periods of time, developing a personal relationship with targets only to betray them in the end, each time losing a piece of yourself in the job. No, audiences want to see someone with a silly-looking sci-fi gun get kicked into a volcano, preferably followed by a bad pun. Both the acting and action in these films is over-the-top, formulaic, implausible, and a hell of a lot of fun. Reality takes a back seat to spectacle.

Mood

“Mood” is a similarly fancy way of saying “what this game features.” (Nothing but fancy language and eveningwear for our undercover agents!) In the case of TCfC!, the mood is that of paranoia and thrills. Most spy movies can be put on a spectrum between those two moods, but nearly all feature some of both. In a genre with false identities, hidden weapons, secret motives, and double (or even triple!) crosses, you have to be careful about trusting anyone or anything. But this is also a game of camp action, which means marrying the mind games with physical thrills. Why simply run away from an enemy agent when you can ski down a mountain away from them, backward, while firing twin pistols? Every scene should either be laden with double-speaking (and double-entendres) or thrilling moments of action. Ideally, both at the same time.

Tropes

Now that we know the high-level theme and mood of TCfC!, where are the details? What are the various tricks and tropes you can flip and push to shoot an oil slick onto the road of your plot, sending your players careening into an abyss… of fun?

Blending Action and Comedy

Parodies like Get Smart aside, there’s not a lot of intentional humor in spy films. Most of it comes from innuendo, clever quips (or Quips), and the occasional raised eyebrow. The humor from the characters is as dry as a martini.

There are plenty of opportunities for metatextual humor, however. The high technology of the ‘60s and ‘70s ranges from charmingly retro to ridiculously outdated, which can look hilarious to modern eyes. Having to hide an electronic safecracker that’s as large as a filing cabinet offers opportunities for humor for the Players, while still being deadly serious from the spy’s perspective.

In fact, that dry “it’s only funny to me” style of humor works well throughout the game. Organizations with clever acronyms like SHIELD and SMERSH might be cool to the people of the time, but an organization called STENCH will have trouble being taken as a serious threat. A plan to contaminate the world’s oil reserves might seem like a serious threat in the 1960s, but we recognize today that this “nefarious” scheme might do some good in the long run.

Like many games in the They Came From series, a good chunk of the humor is going to be inadvertent and metatextual. Unlike the other games, however, the spies in TCfC! are at least somewhat in on the joke, as it were. Characters like James Bond and John Steed draw far more attention to themselves than any self-respecting spy ever should, as if they know they have an audience watching them. They joke as they defeat their enemies, even if no one else is around. For characters who should be invisible to the world around them, the kinds of spies featured in TCfC! are surprisingly aware of the fact that they’re supposed to be entertaining.

But these self-aware or even semi-aware moments work best when they’re infrequent. In general, it’s best to run the game “straight,” as if all the characters consider the latest threat to Western democracy to be a serious and credible danger. Sprinkle in the occasional ludicrous moment or character as the Director, and let the players and the Cinematics bring the rest of the humor into the game.

Innuendo

Actually, let’s talk about innuendo for a moment. Please come sit down next to me and make yourself… comfortable.

No, we mean it. You should be comfortable, particularly with innuendo. While it’s a staple of a lot of spy fiction, it also has a lot of potential to go wrong and make Players uncomfortable — remember that “escapism” is one of the themes we’re going for in TCfC! A simple way to check is to make sure every Player at the table is okay with using or being the target of sexual innuendo. We’ll offer some opportunities for innuendo throughout the book, but if anyone in the group doesn’t feel comfortable with it, toss those options out and present something that’s funny in a different way.

If anyone doesn’t want to use or deal with innuendo, you have two options: don’t use it at all (including through the strategic use of Quips) or present an opt-out option. Players can put cards in front of them saying “no innuendo,” which they can touch at appropriate moments, or they can give a hand signal when they want to get out of an innuendo-laden scene. The point of the game is to have fun, not to offend people or make them feel awkward.

Even if players are okay with it, there are levels to consider. It’s one thing to throw out a double entendre laden with extra meaning, but it’s another to meet a character named Jack Hammer or Harry Bottoms. How much the innuendo extends to the environment of the game itself is up to the group playing. If everyone’s comfortable with such topics, feel free to turn TCfC! into a glorified sex romp with explosions, but again, it’s good to talk this over with the whole group ahead of time and see what will work best.

All that said, innuendo shouldn’t be scary. It’s another rich vein of humor to mine, as Players thrust deep into their dirtiest thoughts to make everyone titter in delight. An otherwise strait-laced mission might quiver with humorous potential, each joke building on each other until the whole thing reaches a climax and explodes with hilarity. Whew, that was exhausting. Anyone have a cigarette?

It shouldn’t have to be said, but just to be clear: Innuendo should never be used to flirt with your fellow Players without their explicit consent. The fate of the world is in your hands, damn it. If you can’t act responsibly, we can find another agent who is able to keep their mind on the mission.

The Mission Structure

A central element of this kind of spy fiction is the mission. The characters get told what world-threatening villain they need to confront, and they go and do it. Of course, it’s never that straightforward. Presumed allies will turn out to be rivals, lethal enemies will reveal themselves as friends, and the mastermind will be one step ahead of the spies until they aren’t.

This heavily formulaic structure can be a huge help to the Director. Not only does it provide an easy way to get Players into the action, but you can plan whole adventures around such a structure: Present the assignment to the character, start the mission with a bang, have two things go wrong, and then build to the climax and ultimate confrontation. Especially if you’re a starting Director, having a clear and easy structure to fill in can really help, particularly if you’re feeling unsure of yourself or just creatively drained.

That said, you can also play with the structure. Occasionally start a mission in medias res, only revealing why the spies are punching escaped Nazis in Brazil after the current scene is over. Maybe the mission briefing is sabotaged, leading to a series of death traps the characters need to escape before they can even start. Perhaps the mission goes terribly wrong, and the characters are disavowed, leaving them stranded in a foreign country with no resources. One of the advantages of using an established structure is that Players will soon expect things to go a certain way, and so they’ll be surprised when a mission doesn’t go according to plan.

Be careful if you consider throwing out the mission structure entirely, though. You can run a campaign where the characters end up being hunted down by their former colleagues, acting as freelance agents as they travel the world to escape their tormentors. That game might be a ton of fun, but that’s not really a spy game anymore in the classic sense. It’s better to bend the structure occasionally to surprise players, rather than discarding it entirely.

Covers and Betrayal

In a spy game, a Player portrays a character, and that character acts like someone else. So, you’re someone pretending to be someone who is pretending to be someone else. Sound confusing? Luckily, most of the spy films of the era only pay lip service to the concept of fictional identities, or “covers” as they’re called in the trade. Yes, most of the films have some example of presenting how the spy in question will go under the name of, say, Arlington Beech, and maybe even give some biographical data of the false identity. But sure enough, as soon as the spy hits the bar, he’ll loudly introduce himself as James Bond.

How important covers are depends on the kind of game you’re running. In a game that emphasizes paranoia, they should be more of the focus. Zero in on every slip-up that a character makes, and make the Players feel like they could be discovered at any moment. On the other hand, if you’re focusing more on thrills, covers can be tissue thin lies, and yet for some reason most people believe them. “Yes, of course, I must have accidentally spelled your name completely differently when I wrote it down. Here are the codes for the nuclear warhead.”

Of course, no matter how you emphasize cover stories, supporting characters are usually surprisingly good at keeping their covers intact. It’s common in espionage films that at least one character will turn out to be a spy with a completely different name (and sometimes, a different accent and personality to boot). Whether or not the characters try to actually, you know, spy on an organization under an assumed name, they will often be blindsided by other characters doing the same thing. The double cross is a major staple of spy films, and one you can use to great effect as Director.

It’s a strange fact, but Players will generally either completely believe anything a supporting character says, or not trust a word that comes out of their mouth, with little middle ground. Mixing truth and lies is something you can use to your advantage, especially when trying to set up an effective double-cross. If the Players don’t trust the character you want to betray them, have the character start telling the truth, or offering useful help and information. Conversely, if Players are trusting the character you want to be a staunch-yet-prickly ally, become secretive and refuse to reveal things as it’s “need to know” or “classified above your security clearance.” Or just change who the ally and who the traitor are to be more interesting when you make the reveal. Sure, it’ll probably create plot holes, but let’s be honest — you’re not playing They Came from [CLASSIFIED!] for intricate mysteries and well-crafted narratives. Just blow something up and move on to the next scene.

World Travel

Spies tend to work for two kinds of organizations: either an explicit national foreign intelligence agency (like MI6 or the CIA), or a vaguely defined intelligence agency with a global remit (like UNCLE or CONTROL). Regardless of which acronym your agents work for, they should be travelling the world to exotic and exciting locations.

The use of “exotic” here is both a goal and a warning. On the one hand, you want to pick locations that are interesting and unusual to the Players. A thrilling car chase in Dublin will elicit more eyerolls than excitement if many of the players struggle with Dublin traffic on the way to work, even if they’re playing American agents. Such Players might find a trip to New York City more exciting, although the traffic is just as bad. Being able to see the world — even the world fictionalized on the silver screen — is part of the fun of spy movies.

That said, while you should feel free to rip off great scenes and moments from your favorite films, do at least some investigation into cities you haven’t personally experienced. Emphasizing the “exotic” in such locales can reinforce negative cultural stereotypes, as unknowing Directors emphasize problematic aspects and elements of these cultures. If you’re going to use a real-world location, try to add at least a dash of real-world research, instead of just what Hollywood thought those locations were like (particularly in the 1960s).

One way around this is to make up fictional countries and cities. It’s a time-honored tradition of spy movies to choose a different name as a stand-in for a real country. Make up a new island in the Caribbean or a little-known Soviet bloc country, and rampage to your heart’s content. Again, don’t use this as an excuse to promote negative stereotypes — calling your war-torn country “Carbombia” is so much worse than using a real country’s culture badly.

Action Set Pieces

At its heart, TCfC! is a game of action, but not just any action. The action scenes should be dramatic, over-the-top, and exciting. You can play any old game to punch someone in the face, but what about punching someone in the face while teetering over the edge of a pool of lava infested with robot sharks? Okay, there might be a few other games that also allow you to do that, but They Came from [CLASSIFIED!] is definitely one of them.

The best way to think about action in the game is to consider them as “set pieces.” In a spy flick, there’s rarely a scene that goes by without a thrilling gun battle, car chase, or grapple over a needed object. That’s your first metric: how often will you have an action set piece? A game that prioritizes thrills might have several action scenes in a game session, while one that focuses on paranoia might only have one or two that are central. As you’re building your mission, consider how many scenes should feature action.

Next, consider what kind of action to incorporate. Shooting guns at enemies can be fun, but if you’re trading bullets at every opportunity, it can get stale. Mix things up a bit. If you consider action in large categories like “combat,” “chases,” and “races,” you can switch between them to keep from getting too stale. Or you can mix and match, such as shooting at an opponent during a car chase.

Also consider adding variations to action moments. This is where things like Complications and Fields come into great effect. It’s one thing to race enemy agents to the control panel before the nuclear missiles launch, but it’s another if the sprinklers have gone off and water is pouring over everything. A gun battle becomes a much trickier prospect if there’s flammable coal dust hanging in the air. And being chased through an open-air market forces characters to abandon cars and rely on motorcycles, scooters, or feet to evade pursuers.

Finally, building off the last section on world travel, incorporate interesting locations. Having a car chase is one thing, but having a car chase through the streets of Rome is another. You can fight over a metal vial of a bio-engineered virus, but fighting over it while balancing precariously on a plank sitting on a tank full of piranhas is definitely more memorable. Create your own interesting locations to make your action scenes really pop, or check out the sets we provide later in this chapter.

So now you have no excuse to not get the tone and theme of They Came from [CLASSIFIED]!

Next week we’ll be here with another game blog! If there’s a game or book you want to see discussed or previewed, just post below!

If we can suggest any book to be previewed… perhaps Wild Hunt or Once and Future?

You can definitely suggest them!

Is _They Came From the Danger Zone_ the 80’s action game of the line a full sized book like [Classified] and Beneath the Sea, or is it smaller like Murder Lake?

Danger Zone! is an expansion book like Camp Murder Lake!. It mainly ties to [CLASSIFIED]!, though there’s some Cyclops’s Cave! connective tissue as well, due to all the Arnolds in it.

That second to last Innuendo paragraph is glorious! Almost left me weak at the knees!

I was once a weak man!

Once a week’s enough for any man.